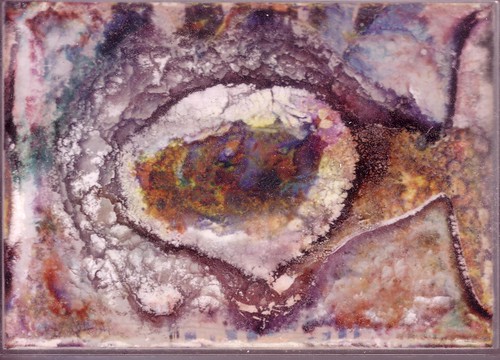

Rain, which I could see pelting through a glassless window, had now set in for the night. It tapped monotonously on floors, on tables and broken chairs as we passed—a gilt clock without its dome and smothered in verdigris stood with its hands forever at twenty to ten on a dripping mantelpiece. Pictures, eighteenth-century prints and maps, askew on the walls, some lying on the floor in their own glass, gazed at us in the light of Mardy’s gaslamp—light that also glanced across a tallboy with jammed and swollen drawers, on a stricken chandelier with half its lustres missing. It danced over a music-room with a concert grand in it; moss choked the blocked teeth of the keyboard. It slid over partitas spread wetly on a stand, on a drenched metronome with its pendulum rusted out to the left, and the water streaming down the walls glittered in it.

—Derek Raymond, How the Dead Live, Chapter 9

I’ve read one of these Derek Raymond novels before, but How the Dead Live strikes some neverbefore heard chord in the Gothic repertory. Half a Chandler knockoff, half a Poe knockoff, it’s completely original in the depth of its existential flagellation. The nameless protagonist, a detective, proves to himself that he’s alive by constantly abrading his personality against the worthless rotten inhabitants of a Kentish village, the way my cat self-medicates her swollen gums.

The 80-room ruin holding pride of place in the minimal plot, the one the narrator describes in the quote: is it a metaphor for the ruined England of the early eighties? Or a metaphor for the creakiness and rot at the heart of the detective novel? I wouldn’t call this one exactly a fresh approach, but there is something to be said for the grand gesture of degradation.